Not so long ago, China’s rise was seen as essentially benign. A growing economy, it was thought, would go hand-in-hand with a liberalising political system. China was, to use the phrase favoured by US experts, becoming a responsible global stakeholder.

But today China is increasingly viewed as a threat. Indeed, many fear that rivalry between China and the US could ultimately even lead to war, a conflict with global ramifications.

In America, a new model is being proposed, one that harks back to the ancient world and the work of Thucydides, the historian of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta.

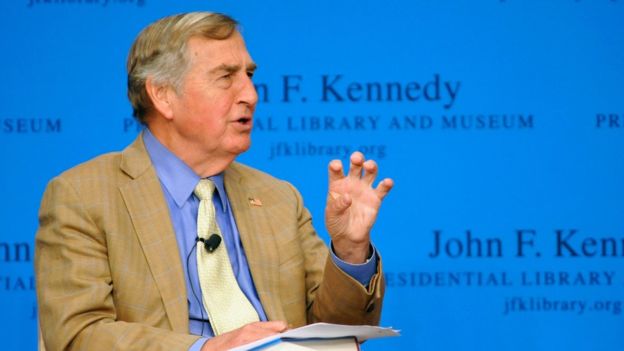

Prof Graham Allison, of Harvard University’s Belfer Center, is one of the US’s leading scholars of international relations. His groundbreaking book – Destined For War: Can America and China Avoid Thucydides Trap? – has become required reading for many policymakers, academics and journalists.

Thucydides’s trap, he told me, is the dangerous dynamic that occurs when a rising power threatens to displace an established power.

In the ancient Greek world, it was Athens that threatened Sparta. In the late 19th Century, Germany challenged Britain. Today a rising China is potentially challenging the United States.

Having reviewed 500 years of history, Prof Allison has identified 16 examples of rising powers confronting an established power: 12 of those led to war. The rivalry between Washington and Beijing is, he says, “the defining feature of international relations today and for as far as any eye can see”.

So asking if the US and China can avoid Thucydides’s trap is no mere academic question. The trap has fast become a major analytical prism through which to view the competition between Washington and Beijing.

Prof Hu Bo for example, of Peking University’s Institute of Ocean Research and one of China’s foremost naval strategists, told me: “I think the balance of power doesn’t support the Thucydides hypothesis.”

Although China’s rise is remarkable, he believes its overall strength is simply not comparable with that of the US. It is only in the Western Pacific, he says, where China stands a chance of matching US capabilities.

But a confrontation there might just be enough to tip these two great powers into war. Not least because China is pursuing the world’s largest comprehensive naval build-up.

“That’s not just impressive today,” says Andrew Erickson, a professor of strategy at the US Naval War College and one of the leading experts on the Chinese Navy, “that’s impressive in world historical terms.”

Its quality is also improving significantly, with larger, more sophisticated warships whose capabilities are, in many respects, getting closer to those of comparable Western vessels.

China’s maritime strategy is also becoming more assertive.

Though the focus of this assertiveness remains, for now, relatively close to Chinese territory, Beijing is trying to raise the costs of possible US interference in a crisis. It wants to be able to keep the United States at bay if, for example, China decided to use force against Taiwan. And the US is determined to maintain access.

But growing Sino-US tensions are also a product of personalities. Chinese President Xi Jinping brings a sense of history, even of destiny, to the rivalry with Washington.

Elizabeth Economy, director of Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, told me that Mr Xi has been a transformative leader with “a much more expansive and ambitious sense of China’s place on the global stage”.

She argues that the most underappreciated element of Mr Xi’s ambition is “his effort to reshape norms and institutions on the global stage in ways that more closely reflect Chinese values and priorities”.

The US is also shifting its position. Washington has branded China, along with Russia, a revisionist power. The US military now regards China as a near-peer competitor, the benchmark against which key air and naval capabilities must be measured.

But while there is a new mood in Washington, it is still very much early days in terms of setting out a new strategy towards Beijing.

Some have spoken of the possibility of a second Cold War, this time between the US and China.

However, unlike the 20th Century Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union, the American and Chinese economies are deeply interlinked. This gives their rivalry a new dimension: a battle for technological dominance.

The giant Chinese telecommunications company Huawei is at the eye of the storm. The US is refusing to allow the company’s technology to be used for key future communications networks, and is pressuring its allies to impose a similar ban.

Washington’s battle with Huawei exemplifies broader concerns about China’s high-tech sector over the theft of intellectual property, illicit sales to Iran and espionage.

Underlying all this is a fear that China may soon dominate key technologies on which future prosperity will depend. Economics and grand strategy are inextricably bound up in this debate, with China intent on becoming the dominant global player within the next decade.

This of course will depend upon China continuing to rise.

There are signs that its economy may be faltering as it clings to its authoritarian model and rejects further market reforms. What might happen if its economic progress slows?

Some argue that Mr Xi might rein in his ambitions. Others fear his domestic legitimacy could be hit, encouraging him to ratchet up nationalism, leading potentially to even greater assertiveness.

The rivalry between China and the United States is real and is not going away. Strategic miscalculation is a clear danger, not least because of the absence of any rule book to help to manage tensions between them.

The two countries are at a strategic crossroads. Either they will find ways to accommodate each other’s concerns, or they will move towards a much more confrontational relationship.

This brings us back to Thucydides’s trap. But Mr Allison emphasises that nothing here is fated. War between the US and China is not inevitable. His book, he told me, is about diplomacy, not destiny.